The Edge Desk

Using design to better optimize the experience of working from home

Overview

Objective // To design a solution to tackle the struggles of working from home, and create a go-to-market strategy for our designed solution

Roles // Product management, system design, research, marketing, finance

Collaborations // Engineering, industrial & graphic design, supply chain & logistics

Outcome

Situation

As the Capstone Project for the MPD2 program, we were tasked with devising a novel solution to address a problem space, falling under the theme of “Something for the Home”. I was part of a team of four, comprising of a mechanical engineer, industrial designer, and graphic artist. Given my background and skillset, I served as product manager for the team.

We focused on the struggles of working from home. Many that we interviewed struggled because of the quick shift to WFH, induced by the pandemic, and employer expectations for similar output. The situation forced many to use makeshift or haphazard work set-ups - especially those operating out of constrained or crowded spaces. And, in terms of the current market, we found that the experience of finding a quick-fix solution was exhausting, both because of market saturation and high price points for modern options.

Given the ambiguity of the prompt, we conducted several rounds of ethnographic research to inspire a solution concept for our capstone project. The path meandered quite a bit as we elicited several potential problem spaces out of our research. After multiple rounds of research and ideation, the WFH space excited us, as a team, the most.

Our solution was the Edge Desk, a vertical workspace capable of effortless personalization enabled by its simple modular design. Taking into consideration the target user we set for ourselves, we aimed to produce this desk at a low cost - for which the manual, yet intuitive, design came handy. What convinced to select this concept was its design, which

Our final presentation was in a “Shark Tank-esque” format, with a judge panel comprising of design executives from an array of areas. To build our case, we constructed a working prototype to demonstrate the concept, along with our intended business model, marketing strategy, and the supporting financials & numbers.

From the final presentation, a furniture company approached us for a licensing deal with intent on continuing where we left off and bringing the Edge Desk to market.

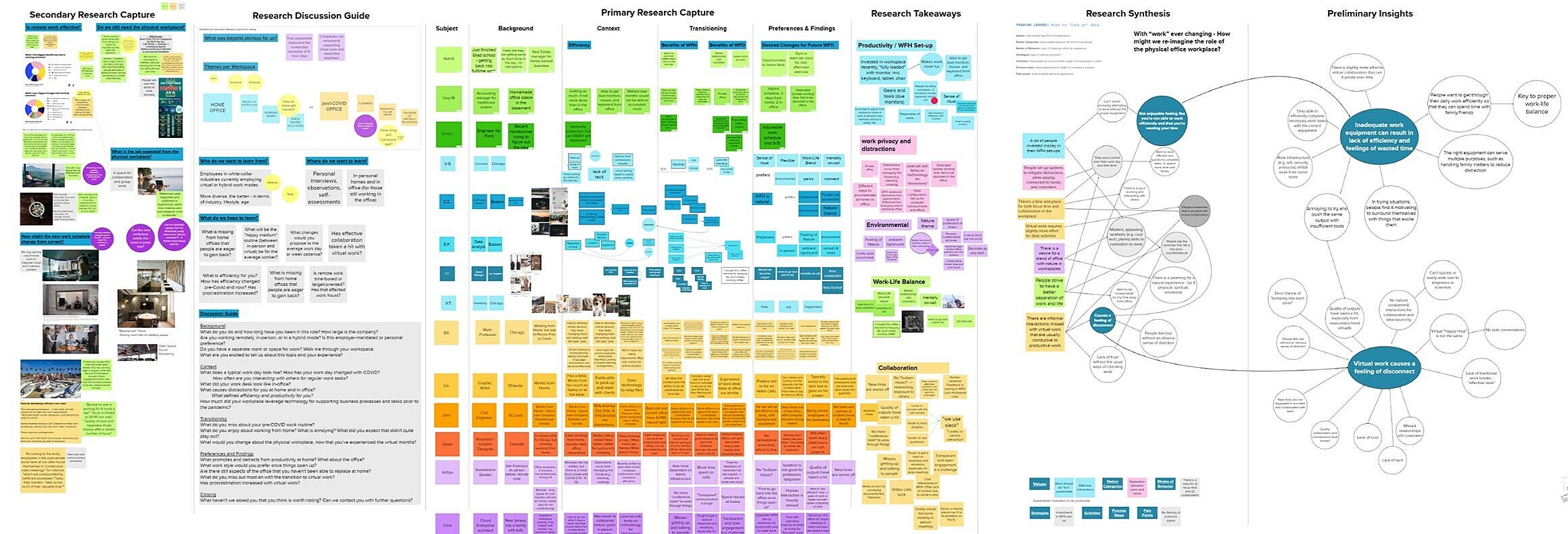

With the pandemic, we found ourselves tasked with the challenge of attempting in-depth personal interviews through impersonal means.

Ethnography is traditionally conducted in-context and with a variety of tools to ensure data being collected encompasses more than just the interviewee’s verbal responses, as a source of novel inspiration is typically found in latent or unexpressed pain points.

Adapting with the times, we used dscout, an online platform aimed to facilitate ethnographic research virtually. Mural was used as a virtual whiteboard to document notes, research, and consolidate takeaways.

Although we anticipated it to be tougher to establish empathic connections and glean insights from contextual clues, FaceTime and Zoom allowed us an instant “teleport” into different worlds. It also helped that, with people relegated to their homes by the pandemic, many were more than enthusiastic to share their daily routine and household pain points.

With a little extra effort and structure in approach, we found that virtual ethnography could be just as valuable.

Testing out the digital whiteboard

Mural turned out to be surprisingly useful as a virtual collaboration tool. I felt that, as a group, we initially missed the structure of something like a shared Google doc for notes, but the free-form format proved to be an interesting way to store research and interesting material.

I personally used it a ton to build out quick idea flow charts (right-most column above) to navigate through the mess of raw research, dig deeper with the five why’s, and consolidate four or five observations into meaningful takeaways and themes.

Process of virtual ethnography

Finding the right balance between structure and spontaneous to elicit worthwhile insights is tough enough in-person, which made an interesting challenge for us to conducting ethnography virtually during lockdown.

We started testing the ethnographic waters with friends and family, and leveraged dscout’s Scout Network for subsequent rounds of interviews as we honed in on themes to explore.

Interview sample size grew smaller as we progressed through rounds, as we felt that the smaller numbers allowed us the time and effort required to extract finer insights.

While conducting interviews rounds through dscout, we heavily leveraged their “screener” feature to vet candidate interviewees. Including more open-ended questions in the screener proved useful for us. It may have pushed some away, but we were able to better evaluate candidate fit up front, which saved us time and money.

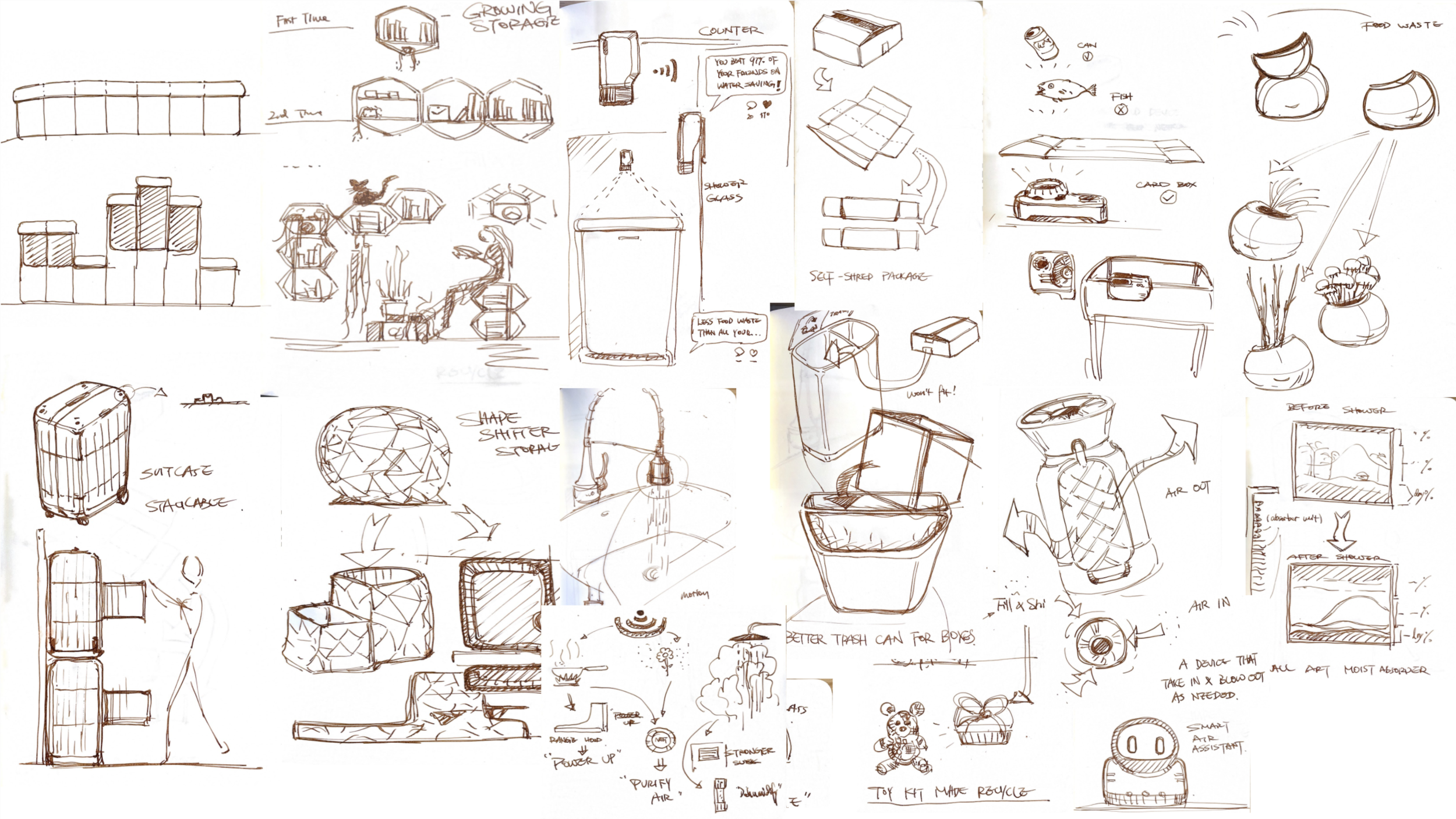

Our research phase narrowed down our focus to three potential problem spaces:

“Evolving Storage”

Insights

This one was born in the numerous complaints around clutter and mess around the house. On top of the frequency, we also noticed that many expressed more nuanced pain points - something preventing an household experience from being perfect.

Opportunity

Our thought was to explore opportunities to expand the level of personalization in storage & organization methods, which is why we chose to term it “evolving”.

“Enabling Simple Sustainability”

Insights

We were happy to see that a lot of people express interest somewhere in the “green” spectrum, whether it be adopting plants for around the home to buying earthworms to jumpstart a compost.

Opportunity

Most had the same pain point - that the feeling impactfully sustainable had a high cost for experiencing. We felt there was opportunity for thoughtful design to ease the average consumer’s entry into the sustainability game and instill initiative to stay playing.

“Protecting against Airborne Intruders”

Insights

No doubt due in part to the pandemic, several of our interviewees expressed concern about inadequate ventilation and build-up of contaminants in their households. More importantly, complaints revolved around the presence (e.g. size, noise) and cost.

Opportunity

If we pursued this space, our plan would have been to explore methods of seamlessly integrating filtration & purification into household environments, focusing on the emotional gratification of keeping loved ones safe.

From interviewing to ideating.

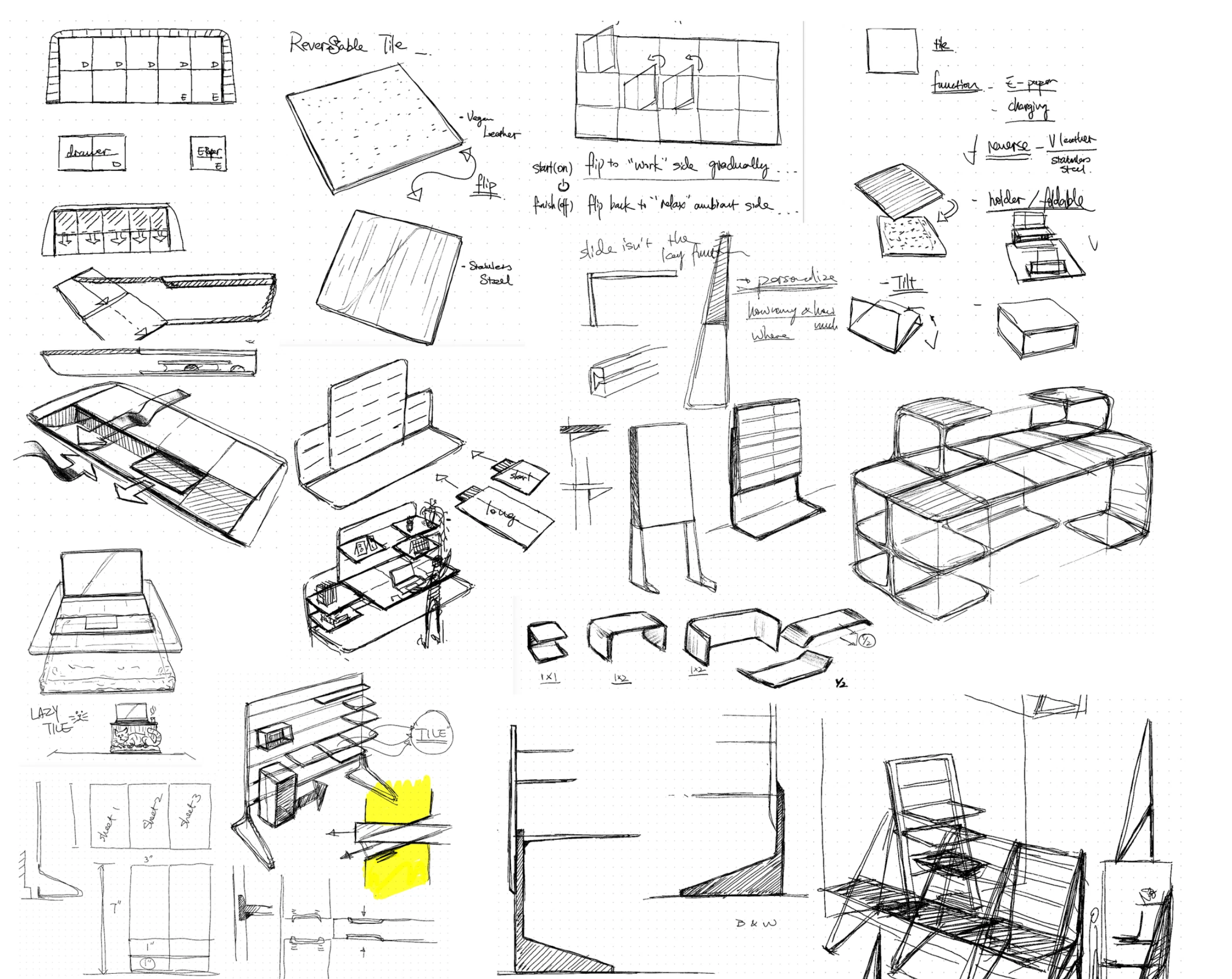

At this point, we (obviously) had some nice-looking sketches, but were stumped on finding the right concept that satisfied our collective definition of novel…

…which meant more research.

“It’s tough working from home”

This time, we thought to approach research a little differently. We went in with a more narrow focus on the work-from-home experience, as we had a hunch that it might be opportunity for design.

Our goal was to find synergy between our three initial problem spaces and our revised direction around the struggles of working from home.

We found that there was significant overlap between two of our problem spaces and the WFH space, and finally found a direction that we all felt had merit to being impactful.

“How might we make working from home more sustainable?”

This new direction also echoed takeaways from our earlier problem spaces.

“Evolving Storage”

What we took as overlap from this problem space was the personalization factor. In both streams of research, we saw that user complaints were more nuanced and centered around small items that kept the product from being perfect.

Given what we had heard and seen, we knew that if we included means for significant user personalization that we would have a product easily differentiated from others in the market today.

“It’s tough working from home”

We found that many struggled with adjusting to a fully remote workstyle, and complained about loss of productivity and waste of time. In particular, we noticed that a large majority of these interviewees lived in more constrained spaces - limited physically by their residence or other family members sharing their work space (e.g. family dining rooms, kitchen islands).

Another notable observation we saw was that expectations, either personal or from a boss, prevented this group from dedicating effort to fixing issues they faced with working from home. Many didn’t think the remote workstyle would last long - and by the time they realized that it was here for the foreseeable future, burnout and a lack of motivation towards work stopped many from investing time to understanding what may work for them as a solution. It was easier to accept and suffer than fight and solve.

It seemed to us that there was opportunity for an intuitive product that required minimal effort for maximum impact to our potential customers. And if we were able to ideate a solution that tackled the most restrictive use case, we would have a product that many others would find useful.

“Enabling Sustainability”

The overlap we saw between these two problem spaces was more so from a conceptual perspective. We chose sustainability as one of our problem spaces because of the struggles echoed across many around finding ways to be sustainable and feel useful.

From our WFH research, we noticed that people had the same theme of complaint. The sudden shift to a remote workstyle stunned many, and prevented people from understanding what they individually needed to ensure productivity and efficiency at home.

Our vision was to create a solution that made working from home more sustainable, from the standpoint of energy management and mental stamina.

Who was our target user?

Renters living in constrained spaces (e.g. apartments, small family homes)

Working professionals aged 25-44

Likely to be living with others (e.g. roommate, significant other, family)

Values productivity and efficiency, as a result of mentality instilled from current work practices

“Why renters?”

We thought it would be interesting and a challenge to place a restriction on our creative process - that the solution needed to avoid invasive mounting.

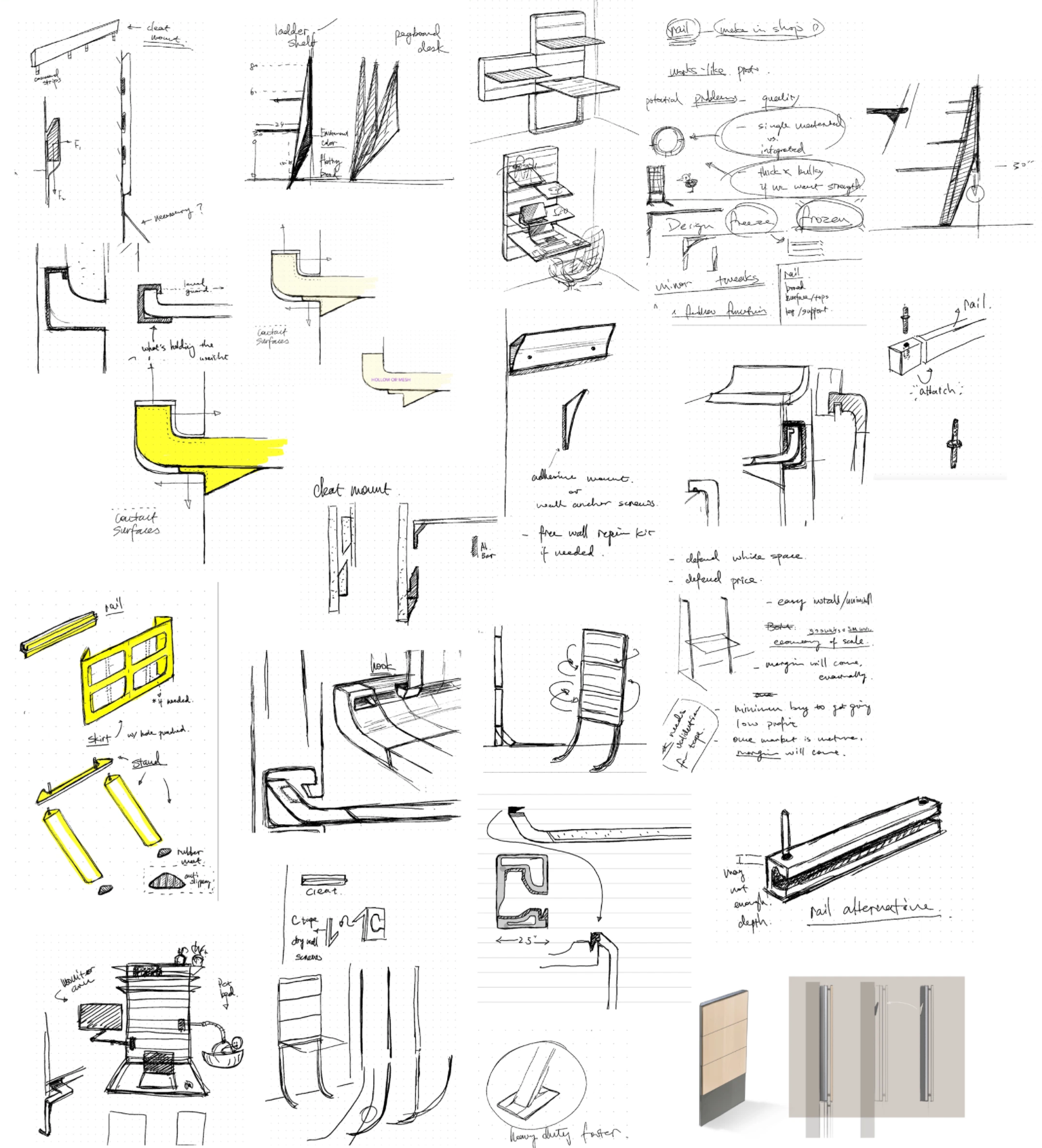

With stronger clarity on direction, we felt comfortable circling back into the drawing space to conceptualize.

By chance, we found inspiration in pegboards.

We tried to find inspiration, in tangent physical spaces around the house, from other successful means of achieving efficiency through simplicity.

Our final spur of creativity came from examining tools that make the “handyman dad” well-equipped for projects at home. Our target user and this persona shared similarities, in that both are looking for easy, multi-functional solutions that require low effort to install and use.

The pegboard resonated strongly with us because of how it leverages simplicity and modularity for efficiency. At this point, we knew that we had our core inspiration, and that the task now was figuring out how to extend the concept into a work desk.

Our Final Concept

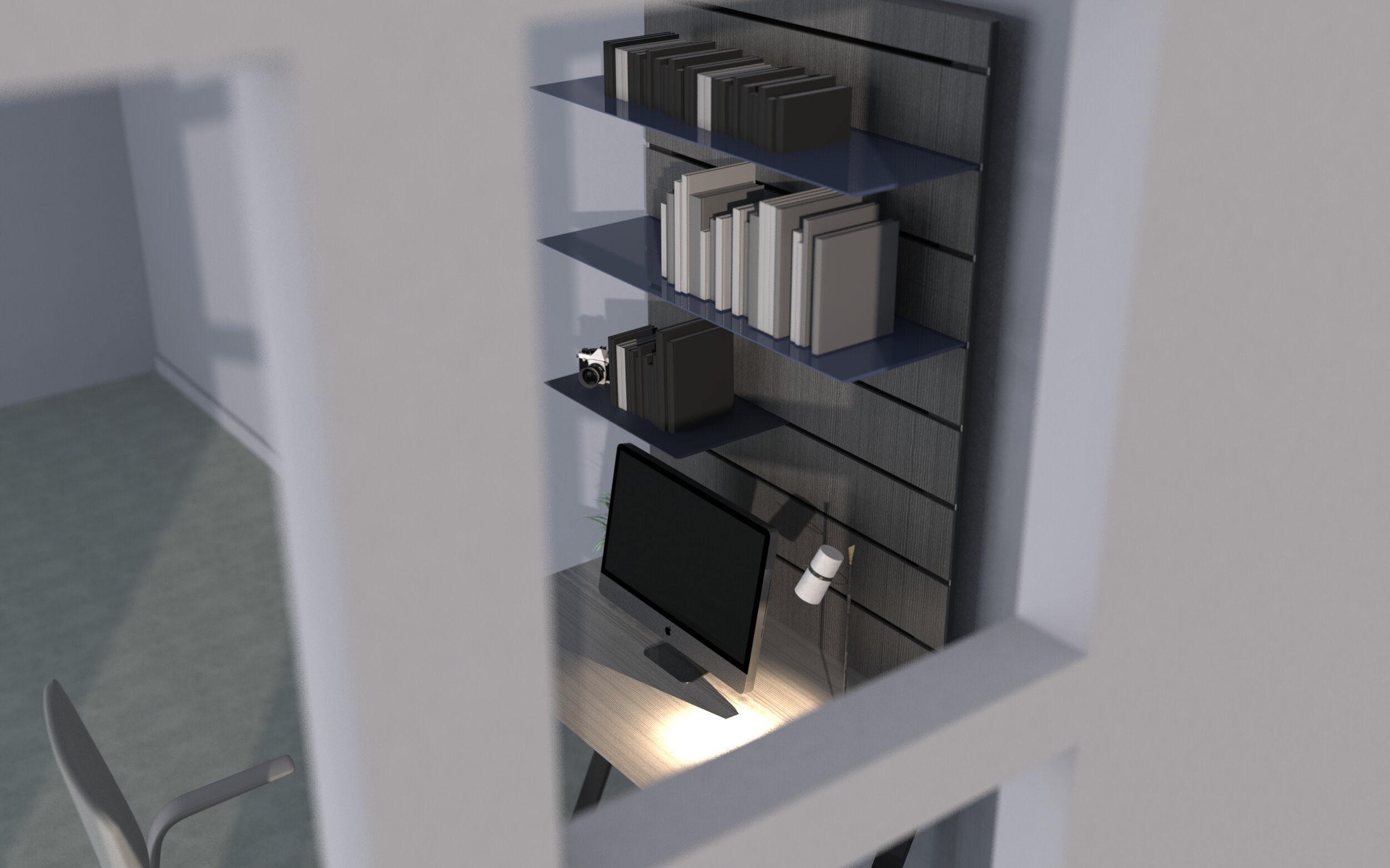

The culmination of our efforts was the Edge Desk, a modular vertical workspace for the space-constrained WFH employee.

“Build-a-block”-style assembly enables easy and intuitive installation

Design allows for movement of surfaces for quick, hassle-free personalization

Novel rail design offers storage with inclusion of a nook to hang surfaces on when not in use

What convinced us to pursue?

Very Personalizable

The design renders itself very useful for quick personalization, as users would have the ability to move and adjust surfaces between rails. And given the simplicity of the rail design, it would be very easy to release a bevy of surfaces for use with the Edge Desk.

The combination of multiple rail positions along with a variety of surfaces yields numerous permutations of positions to support different work styles and personalized work set-ups.

Non-Invasive Assembly

One of the key differentiators of this design is the leaning approach. As opposed to pegboards and other vertical workspaces on the market currently, designing the Edge Desk to lean avoids any drilling or invasive assembly methods - which caters directly to the renter crowd.

The desk stand and the backbone were specifically designed, from an engineering standpoint, to ensure sturdiness under applied loads.

Minimal Footprint

We chose to build a vertical workspace specifically because of our chosen target user. At max, the design extends into its space 28” - which allows it a small footprint in any space it is placed in.

The vertical form factor also proved useful for easily supporting multiple work styles - between sitting, standing, and sharing. The built-in feature to “fold away” surfaces also helps greatly in aiding the minimal footprint.

The Financials

We used market research and an “Aware-Trial-Available-Repeat” (ATAR) estimation approach to size out our potential Year 1 market of roughly 3200 people.

Our selected materials and dimensions yielded a Bill-of-Materials cost of $174.

Taking into account our target user, our BOM cost, and how we wanted to enter the market at a low-cost price point, we chose the Year 1 retail price at $399.

As an investment from the panel, we asked for a hypothetical investment $300,000 - which would help float the company through the development of extension surfaces along with refinement of the base concept. If all went well, this investment would accelerate our break-even point to Year 2, from Year 4.

Key Takeaways

Don’t be afraid to go in circles

The design thinking process is anything but linear. Initially, it stressed us when we frequently needed to circle back to a previous stage of thinking, but over the course of the program I realized that it is natural to swing between phases as it ensures that the final product is truly tweaked to user needs.

Less is more

This one was a logical takeaway, but I underestimated the value of simplicity. Coming from a consulting background, I was accustomed to being overly cautious - ensure that all bases were covered through detailed content.

I noticed that this doesn’t carry over as well to the design world. Adhering to design principles is not only expected by fellow designers of work output, but by work presentation. Simplicity was key, and it forced us to cut down to the minimum viable element - which greatly helped throughout this project.

How to manage creativity

As the project manager, I took a more methodical and structured approach, at first, to organizing the group and our work - similar to how I did at PwC. I quickly realized that a creative process, like the one we were following, needed space to breathe and stretch its wings - structure could very quickly stifle ideas in infancy. I saw that there was merit in following tangential thoughts, and how sometimes a “distraction” circled back and yielded a conclusion that we took forward.

Importance of prototyping

Probably one of the base tenets of the product design world, but materializing thoughts, in any way and for any purpose, went a long way in navigating the nebulous mission of inventing a new product.

Whether we needed to test out a mechanical design or a presentation template, starting down the path allowed us to better evaluate the approach and uncover issues earlier in the process.